Development Issues No. 10: International financial flows and external debt

The Development Policy and Analysis Division at DESA has prepared a series of policy notes to review current trends in the global economy with the intention of stirring debate about the urgent need to create an enabling international environment for sustainable development. This note reviews current trends in international financial flows.

Achieving the SDGs requires an enhanced global partnership to bring together governments, the private sector and citizens to mobilize available resources. As stated in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) of the Third International Conference on Financing for Development, raising necessary funds is key to realize the 2030 Agenda for sustainable development. Among them, cross-border financial flows are important sources for supporting the achievement of the SDGs, particularly in developing countries. Long-term financial flows can support investments that are a critical engine for productive employment and growth for sustainable development (SDG 8). They can further support social inclusion and environmental sustainability by providing proper incentives to investors.

This note reviews recent trends in international financial flows and examines three types of financial flows that can support long-term investments; namely, foreign direct investment (FDI), official development assistance (ODA) and remittances. The discussion is followed by an examination of debt sustainability, as an issue of recent concern due to a creeping increase in debt servicing in some developed and developing countries. From a review of these issues, the note concludes by restating the need for a renewed commitment and enhanced efforts by the international community to support financing for sustainable development.

Overview: Resource transfers and financial flows in developing countries

Net transfer of resources from developing countries continues to be negative, which means that capital has been flowing out of these countries (see figure 1). In 2016, net transfers from developing countries as a whole are estimated to have reached about $500 billion, a slight increase from the 2015 level.

But the global picture masks significant regional differences. While net transfers were slightly positive for a few developing regions in 2015 and 2016, other regions recorded negative net transfers. In particular, East and South Asia experienced large outflows of portfolio and other investments (e.g. bank lending). On the whole, net financial flows -- the sum of direct, portfolio and other investments -- to developing countries were negative in both 2015 and 2016, in response to a slowdown in the growth prospects of large developing countries and, more recently, due to monetary tightening in developed countries. More fundamentally, portfolio investors in developed countries who were seeking “safe” assets cycled back a large percentage of the investments they had made in developing countries in the first half of the 2010s. International banks, particularly European, facing deleveraging pressures since 2008, also reduced cross-border bank claims. In response to capital outflows, many central banks in developing countries started drawing down their foreign currency reserves to help stabilize exchange rates in 2015 and 2016, in clear contrast with the build-up of foreign reserves taking place at the global level in the previous years.

As seen above, net financial flows to developing countries turned out to be negative in both 2015 and 2016, but the relatively high levels of foreign reserves and greater exchange-rate flexibility in developing countries have provided a buffer in coping with capital outflows. The global economy, however, may face higher volatility in capital flows in 2017 and beyond, especially if policy uncertainty in large developed countries increases.

Overall, the reversal in flows in 2015 and 2016 and the predicted higher financial volatility in 2017 threaten the fulfillment of poverty eradication and other development commitments that the international community agreed in the 2030 Agenda for

Sustainable Development.

Foreign direct investment

In the framework of the AAAA, FDI is identified as a mechanism that can facilitate sustainable development and the implementation of SDGs when investments are directed to development-enhancing sectors, such as resilient infrastructure and renewable energy. Compared to portfolio investments, FDI provides a more stable stream of investment. The volume of resources to developing countries, however, decreased sharply in recent years; FDI fell to an estimated $209 billion in 2016, from $431 billion in 2015. This decline reflected fragility of the global economy, persistent weak aggregate demand, sluggish growth in some commodity-exporting countries, and a slump in profits earned by multilateral enterprises.

There are a few concerns about recent trends in inward direct investment to developing countries. First, while its flows

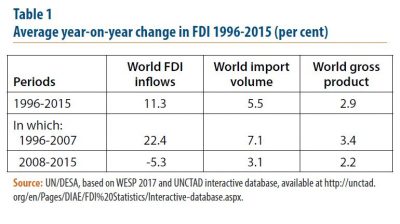

continue to be relatively high and stable, there are wide regional differences. East and South Asia attracted more than 70 per cent of global FDI in 2015, the latest year for which data are available, whereas FDI to LDCs, SIDS and LLDCs accounted for a mere 8.4 per cent. Second, FDI recorded as cross-border mergers-and-acquisitions in recent years were often attributed to corporate reconfiguration, with large movements in the balance of payments, but little change in actual expansion of productive investment. Third, the average annual growth rate of FDI at the global level became negative after the crisis in 2007-2008. These trends contrast sharply with the experience in 1996-2007 when world FDI was growing much faster than WGP and global trade (see table 1).

Overall, FDI flows are falling short of commitments made as part of the AAAA, which calls for providing additional incentives for the expansion of FDI to unfunded or under-funded countries and priority sectors, while ensuring the greatest contributions to the SDGs and other national goals. Improving the flow of FDI to developing countries will likely require additional actions from the international community to provide insurance, investment guarantees or other kind of instruments to encourage and support greater productive investments in developing countries with particular attention to the LDCs, SIDs and LLDCs.

Official Development Assistance

Public sources of external financing can contribute to finance sustainable development by addressing community needs and the provision of public goods, which are seldom met by profit-motivated private investment. Public resources are used to finance health and education and to fund infrastructure investment. Many developing countries, including LDCs, SIDS and LLDCs, rely on ODA and other external public and private sources to complement their efforts in providing these basic services and other internationally agreed SDGs.

ODA from the DAC member countries of OECD reached $146.5 billion in 2015, an increase of 6.6 per cent over 2014 (in constant prices). This increase, however, was largely owed to additional spending on the situation of refugees. The $146.5 billion represented about 0.3 per cent of total GNI of OECD member countries, far below the agreed target of 0.7 per cent. Beyond the DAC members, international public finance has increased due to enhanced South-South cooperation. DESA estimates that concessional South-South cooperation have reached over $20 billion in 2013 and much higher figures in the following years.

LDCs remain heavily dependent on concessional finance, which represented about 68 per cent of total external finance to LDCs in 2014, the latest year for which comprehensive data is available. Bilateral ODA to LDCs increased in 2015 by 3 per cent over 2014, amounting to $27 billion. In 2015, concessional finance to LDCs was $42 billion, representing 0.09 per cent of their total GNI, which is also significantly below the UN target of 0.15-0.20 per cent. On the other hand, the composition of ODA to LDCs has shown positive signs of change. Bilateral ODA targeting climate-related interventions in LDCs—primarily in the energy, water and transport sectors—has been increasing: $4.4 billion on average per year during 2012-2014, as compared with $131 million during 2002-2005. Bilateral donors have become more focused on climate adaptation activities in LDCs, allocating 43 per cent of their ODA in adaptation versus 39 per cent in mitigation.

SIDS continue to face challenges in attracting private finance, and they also have difficulties in accessing concessional finance.

Concessional finance to SIDS has decreased in the last five years, representing 22 per cent of total external finance in 2014. The only area where ODA is increasing in this group of countries is climate-related finance, amounting to $1.1 billion in 2014. These flows aim at building resilience to climate and disaster events, primarily targeting adaptation activities.

The Addis Ababa Action Agenda reaffirms ODA commitments and calls for giving priority to “those with the greatest needs and least ability to mobilize other resources” in order to overcome the challenges to achieve sustainable development with “no one left behind”. The donor community is expected to double and triple its efforts to promote a larger, stable and more effective allocation of ODA in line with international commitments. To achieve these goals there is a need to expedite efforts to; (i) improve aid flows by providing recipients with regular and timely information on planned support in the medium term (predictability); (ii) align aid-supported activities with national priorities by reducing fragmentation, accelerating the untying of aid, and promoting country ownership, and; (iii) provide the most concessional resources to those with greatest needs and the least capacity to mobilize other domestic and external resources.

Remittances flows: how sustainable can they be?

Worldwide remittance flows in 2015 are estimated to be over $601 billion, from which developing countries received about $432 billion, only 0.4 per cent above 2014. Still, remittances figures represent a stable and growing source of finance and nearly three times the amount of official development assistance (ODA) flows to developing countries. The actual size of remittances, including unrecorded flows through formal and informal channels, is estimated to be significantly larger.

Workers’ remittances to their countries of origin are the product of income earned by migrant workers and an important source of external financing in many receiving countries. Migrants send remittances to their families supporting an increase in effective demand for consumption as well as for increasing investments in housing, health, education, and small business enterprises in local communities. To the extent that remittances are received largely by poor households, their contribution to poverty reduction is significant, which in turn can help to pave the road towards the achievement of the SDGs. Remittances also provide increased liquidity and foreign exchange to receiving countries facilitating an increase of imports in goods and services. These flows constitute more than 10 per cent of national income for many countries, including a few European countries. Even in the context of larger countries, remittances are an important source of finance. In 2015, the top four recipient countries were India, China, the Philippines, and Mexico. Remittances to Mexico, for example, were in the order of $24.8 billion in 2015, larger than $23.4 in oil revenues received. Similarly, the Arab Republic of Egypt has been a top remittance receiver in the MENA region, with remittances of more than three times the revenue from the Suez Canal.

Remittances to developing countries have grown steadily and have proved to be more stable than other external flows. Remittances have also helped to counterbalance the volatility of other capital flows to developing countries (see figure 2 below). Yet, innovative policies directed to enhance the potential of remittances, by providing wider access to credit, reducing transactions costs and improving the formal status of migrant workers, to expand their contribution to sustainable development.

High-income countries are the main source of remittances. The United States was the largest, with an estimated $ 56.3 billion in 2014. Saudi Arabia was the second largest, followed by Russia, Switzerland, Germany, United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. In total, the six Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries accounted for $98 billion in outward remittance flows in 2014.

Uneven remittance flows at the regional level

Weak global economic growth had a toll on remittances to developing countries. They are estimated to have increased only slightly to $442 billion in 2016. The modest recovery in 2016 was largely driven by an increase in remittances to Latin America and the Caribbean mainly due to the recent recovery of the U.S. economy.

In contrast, other regions are seeing a decline in the earnings sent home by migrants. Low oil prices continued to be a factor reducing the flow of remittances from Russia and the GCC countries. In addition, anti-money laundering efforts have prompted banks to close down accounts of money transfer operators, diverting activity to informal channels. Similarly, policies favoring employment of nationals over migrant workers have discouraged demand for migrant workers in the GCC countries.

In 2015, as a consequence of the economic slowdown in Russia and the depreciation of the ruble, there was a decline in remittances from Russia to the Commonwealth of Independent States. On the other hand, there was a rebound in Latin America benefiting mainly Mexico and Central America. Remittance flows to Mexico increased by over 8 per cent year-on-year in the first half of 2016 (WESP 2017). There was also continued growth in South Asia despite low oil prices in the GCC countries, while remittance flows in the Middle East and North Africa and in Sub-Saharan Africa regions stagnated.

It is estimated that growth of remittances to developing countries would remain at about 3 percent in 2017. Developing regions other than Latin America and the Caribbean are projected to grow at 2 percent or lower. Weak growth in remittances can represent financial challenges for millions of families that rely on these flows; in turn, this can seriously impact the economies of many developing countries whose prospects for strong economic growth and achievement of the SDGs can be further threatened.

Notwithstanding the fact that the transfer costs of remittances have continued to decline, they remain high in some regions. In sub-Saharan African countries, for example, remittance transaction cost averaged 9.5 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2015, with costs in some corridors between South Africa and nearby countries as high as 18–20 per cent. It is important to keep in mind that the AAAA includes a commitment to reduce the average transfer cost of migrant remittances to less than 3 percent by 2030 (WESP 2017).

Going forward, regaining stronger growth trends in developed countries would help to enhance remittances and the prospects for sustainable development. The regularization of the legal status of millions of migrant workers around the world can provide greater stability to the hiring of workers in destination countries, contributing to improve their employment and working conditions and support effective demand. Conversely, increased hostility towards refugees and migrant workers will jeopardize the contribution of migrant workers to the wealth creation of developed countries and may compromise the regular flow of remittances to finance sustainable development in many developing countries.

Debt sustainability

Debt financing is an important source for sustainable development, both by public and private actors; yet high debt levels can carry risks for economic growth prospects, financial stability and for charting sustainable paths of development. According to IMF/BIS estimates, the combined debt of Governments, households and non-financial firms reached an all-time high of $152 trillion in 2015, or 225 per cent of world gross product (WGP). Private sector debt accounts for approximately two thirds of the total debt stock.

While private sector debt in developed economies remains at the centre of the global debt overhang problem, the post-crisis period has been characterized by two major trends: (1) a significant increase in public debt in developed economies; and (2) a private debt boom in several large developing countries, such as Brazil, China and Turkey. The substantial rise of public debt levels in developed economies reflects large revenue losses as well as fiscal stimulus programs and banking sector bail-outs in 2008-10, but also the low-growth environment that has prevailed in the post-crisis years. Subdued nominal GDP growth has also hampered the deleveraging process in the private sector of developed economies, which has been uneven and slower-than-expected.

Public debt in developing countries has risen modestly since the global financial crisis and generally remains much lower than in developed countries. Yet, the rise in private sector debt in a few emerging economies has been facilitated by extraordinarily loose global financial conditions as central banks in developed countries employed a range of conventional and non-conventional monetary policy tools to revive their economies. Much of this increase in debt has been concentrated in the non-financial corporate sector of large emerging economies.

Developing countries

Developing countries’ external debt was estimated to have averaged 26 percent of GDP in 2015 (figure 3), which represented a very modest increase over previous years. External-debt-to-GDP ratios in developing countries declined significantly in the second half of the first decade of the new millennium, mainly due to high GDP growth, debt relief and countercyclical policies.

Developing countries’ external debt was estimated to have averaged 26 percent of GDP in 2015 (figure 3), which represented a very modest increase over previous years. External-debt-to-GDP ratios in developing countries declined significantly in the second half of the first decade of the new millennium, mainly due to high GDP growth, debt relief and countercyclical policies.

Moreover, the external debt stocks of low- and middle- income countries in absolute terms declined in 2015 for the first time in more than two decades. They fell by 6 per cent, to reach $6.7 trillion dollars, mainly due to net debt outflows in conjunction with year-on-year exchange adjustments between the currencies in which external debt is denominated. Outflows were driven by an 18 percent contraction in short-term obligations compared to 2014. China, having over 21 percent of the combined external debt stock of low- and middle-income countries, drove the global trend. Excluding China, external debt stock totaled $5.3 trillion at end-2015, only marginally below the end-2014 level.

As debt stocks declined, external debt burdens in low- and middle-income countries remained moderate in 2015, with a ratio of external debt to GNI around 26 per cent. The ratio of external debt to exports averaged 98 per cent, a figure slightly above the prior year average of 92 percent. These ratios, calculated on the basis of the current U.S. dollar value of GNI and exports should be carefully interpreted since they mask increased debt service costs arising from the appreciation of the U.S. dollar.

While the overall debt situation of developing countries remains relatively benign, risks to debt sustainability exist in some developing countries. Three low-income countries are currently considered to be in debt distress by the IMF and the World Bank, and an additional 17 countries are at high risk of debt distress, as compared to 13 countries in April 2015. More recently, the sharp fall in commodity prices and the slow-down in economic growth have forced a number of countries to seek financial assistance from the IMF and the World Bank. In particular, lower middle-income countries such as the SIDS, are hampered by limited economic activity and a small tax base with high debt-to-GDP ratios.

The post-crisis experience in developed economies has underscored the strong linkages between private sector and public sector balance sheets, while also illustrating the difficulties in ensuring a smooth deleveraging process. For the corporate sector in emerging economies, significant risks are associated with a potential rise in borrowing costs. A faster-than-expected tightening of monetary policy in the United States could trigger substantial capital outflows from emerging markets, which will further strengthen the dollar. This would make companies in emerging economies particularly vulnerable if the cost of borrowing in dollar denominated debt increases.

On the whole, the rise of corporate debt in emerging markets in recent years can become a relevant risk to the global growth outlook. Some of the larger developing economies, including China, have seen rising leverage in non-financial firms in recent years. While rising leverage may not be harmful when it reflects deepening of financial markets, it could be a risk if corporate profitability deteriorates in conjunction with debt accumulation, putting balance sheets on a fragile footing (WESP 2017).

Developed countries

Recent quarterly data on external debt of high-income countries confirm that their debt levels are on average 2 to 3 times higher than in low- and middle-income countries. This is mainly due to the 2007-2009 financial crisis -- the deepest and most synchronous crisis in the world since the 1930s. At the end of the second quarter of 2016, the highest percentage ratios of government gross debt to GDP among the EU-28 were in Greece (179), Portugal (132), Italy (136), Belgium (110), Cyprus (109) and Spain (101) (see Figure 4).

Indeed, in 2008, the volume of resources committed by IMF programmes to European economies was the largest in the IMF’s history, with total commitments hitting an all-time peak as a share of WGP. From 2008 to the present, the IMF loaned more than $200 billion dollars, with two-thirds going to advanced economies such as Greece, Iceland, Ireland and Portugal. The crisis in Europe fostered the trend towards bigger debt programmes and led to a concentration of IMF loans to Europe; by 2013 almost 80 per cent of its outstanding loans were owed by European countries.

Indeed, in 2008, the volume of resources committed by IMF programmes to European economies was the largest in the IMF’s history, with total commitments hitting an all-time peak as a share of WGP. From 2008 to the present, the IMF loaned more than $200 billion dollars, with two-thirds going to advanced economies such as Greece, Iceland, Ireland and Portugal. The crisis in Europe fostered the trend towards bigger debt programmes and led to a concentration of IMF loans to Europe; by 2013 almost 80 per cent of its outstanding loans were owed by European countries.

Potential impact on countries in the future

The high and rising level of global debt presents a challenge for the global economy going forward. While recent empirical research has not identified a clear debt threshold above which medium-term economic growth is significantly compromised, there is some evidence of a link between the debt trajectory and the growth performance. Private sector credit booms have been a key factor associated with financial crises in the past.

For some EU countries, debt sustainability issues have been manifesting for some years now. Further, credibility issues may arise in cases when private creditors would be asked to agree to a debt restructuring and share part of the burden in future bailout programmes. The IMF may face larger demands for new loans, including by emerging countries with sizable debt burdens.

The risks towards unsustainable debt levels may further come from different sources. In recent years, firms and banks in emerging economies have borrowed at low international interest rates when their currencies were stable or appreciating against the dollar. In addition, current account deficits have returned in these countries, together with domestic credit booms and currency overvaluation. Already, an appreciating US dollar coupled with domestic currency depreciations in a few emerging markets has increased debt burdens since 2013.

Concluding remarks

The current economic (and political) environment makes it difficult to ensure sufficient external financing for achieving the SDGs, as envisaged in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. It is imperative that the international community fosters an enabling environment to facilitate increased, stable and sustainable finance to support countries’ efforts towards sustainable development.

Private-cross border flows have been dominated by short-term portfolio investments, as reflected in the high volatility of international financial flows. FDI, which represents a longer-term commitment to the development of countries, has largely been attracted by East and South Asia, but not by under-funded countries such as LDCs, SIDS and LLDCs, thus falling short of the commitments agreed in the AAAA. A revamping of the international financial system is necessary in order to increase the flow of FDI with the aim of aligning private incentives with the SDGs. Insurance and investment guarantees are two examples of measures that would encourage greater international investments towards priority countries

The AAAA also reaffirms ODA commitments. Official donors need to strengthen their international commitments for sustainable development by meeting the two UN targets for ODA, as well as aligning ODA with the national priority of recipient countries to make aid flows more stable and predictable.

On external debt, risks of debt sustainability are high for a few developed countries with significant debt burden and, for some emerging economies. The current low growth trend makes it particularly difficult for countries to reduce their debt-to-GDP ratio, which reduces the policy space needed to engage on structural transformation for sustainable development. In this light, it is important that these economies enhance their long-term growth strategies by building climate resilience through long-term investment in infrastructure and human development. Clearly, greater policy coordination at national and international levels is urgently needed to recover sustained economic growth and productive investments necessary for enhancing sustainable development paths.

Similarly, stronger global growth can help to enhance a sustained flow of remittances. The regularization of the legal status of millions of migrant workers around the world would provide greater stability to the hiring of workers in destination countries, while also contributing to support effective demand and the employment and working conditions of immigrants. If hostility towards refugees and migrant workers continues to grow, increased insecurity may jeopardize the contribution of migrant workers to the economy of developed countries and may compromise the regular flow of remittances to finance sustainable development in many developing countries.

Follow Us