World Economic Situation and Prospects: August 2024 Briefing, No. 183

Two decades of Eastern Europe’s membership in the EU

Two decades of Eastern Europe’s membership in the EU

On 1 May 2004, eight countries from Eastern Europe – the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia – the group often referred to as EU-8, along with Cyprus and Malta, became full-fledged members of the European Union (EU). This event is often called the “Big Bang” enlargement of the EU, with the set of pre-existing members being referred to as the EU-15. To be admitted to the EU, these eight Eastern European countries introduced widespread structural changes, aligned their domestic institutions with the EU’s common market rules and regulations, adopted EU’s acquis communautaire and reoriented their trade, finance and investment flows towards Western Europe. At the time of accession these countries were functioning market economies increasingly integrated into the European production chain, benefitted from multiple EU funding programmes within the framework of pre-accession financial assistance, and even de-facto had partial acess to EU labour markets.

Trends in economic growth and gains in productivity

The “Big Bang” enlargement of the EU in 2004 led to significant industry level adjustments both in the EU-15 and in the EU-8 member states, as it led to a more intense competition in certain sectors. The Eastern European countries offered a much cheaper labour force, less expensive agricultural and raw material inputs, and therefore benefitted from cost competitiveness both in intermediate and final goods markets in Europe. At the same time, multinational corporations of the EU-15 gained access to a new large market with population approaching 100 million and rapidly growing consumer and investment demand.

Over the 20 years of EU membership, the EU-8 saw impressive output gains, steadily maintaining 2–3 percentage points differential in average GDP growth compared to the EU-15 countries, thanks to large foreign direct investment (FDI) inflows, deepening production and trade integration with the Union, and significant EU funding. In fact, gains in per capita output in the EU-8 from 2004–2023 noticeably exceeded those achieved by a comparison sample of developing countries with a similar level of income in 2004 (figure 1a). The largest Eastern European economy, Poland, has more than doubled in size by 2023; the Baltic States and Slovakia also saw impressive gains. The region has been gradually converging towards the average EU per capita output levels; the speed of convergence, however, has slowed somewhat in recent years (figure 1b), as the initial gained competitiveness waned, and production costs increased.

The path of economic development during those 20 years was not smooth, as there were numerous setbacks and headwinds, including the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, the European debt crisis of 2012, the economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, and, most recently, the war in Ukraine. These shocks affected each member of the EU in an individual manner.

Moreover, the pattern of growth itself was not always sustainable. Prior to the global financial crisis of 2008–2009, domestic demand became the main driver of growth in the region, as most Eastern European economies experienced a credit boom fuelled by cheap foreign exchange loans, (in particular, in euro and in Swiss francs), including mortgages. Short-term foreign borrowings by domestic banks were channelled into long-term loans. Despite the strong export performance, the countries ran large current account deficits financed by cross-border capital flows. As those flows collapsed in 2008 and Western European banks sharply reduced their exposure to the region, domestic consumption and fixed investment came to a virtual standstill.

Along with the collapse in external demand, this caused a recession in most EU-8 countries. Credit crunch in Eastern Europe lasted for years, prompting the adoption of public stimulus to rekindle growth. The appreciation of Swiss franc in 2015 seriously hit the Eastern European banking sector. The problem of outstanding euro- and Swiss franc denominated mortgage loans in some EU-8 countries is still not completely resolved.

Foreign direct investment inflows, technological modernization, and trade integration

Massive inflows of FDI, predominantly from Western Europe, that started prior to the accession were critical for economic modernization of EU-8 countries. During the first decade of their EU membership, average annual FDI inflows in these countries reached 4–5 per cent of GDP, far above the global average. These inflows were facilitated by ongoing privatization, improved regulatory environment aligned with the EU rules, deepening trade and financial links and improvements in the infrastructure connections with the rest of Europe. Macroeconomic stabilization, in particular, reducing the initial skyrocketing inflation and exchange rate stabilization, and compliance with the fiscal deficit and public debt constraints of the Stability and Growth Pact also played a favourable role. In addition, many EU-8 countries adopted FDI-friendly domestic policy incentives, especially for greenfield investments, such as lower corporate and value-added tax (VAT) rates, tax credits and tax holidays, and higher capital depreciation rate allowances for tax deductions. Some countries provided subsidies or regulatory concessions to foreign investors.

Since 2004, total stock of both private and public capital in EU-8 had expanded at a much faster rate than in other EU countries. Especially impressive gains were recorded in the Baltic States and Poland. An important case in point is the automotive industry in Eastern Europe. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia received both brownfield and greenfield investments from leading carmakers such as Audi, BMW, Citroen, Jaguar, Land Rover, Kia, Mercedes, Peugeot, Renault, Toyota Motors, and Volkswagen. The Czech Republic and Slovakia, especially, became automotive industry hubs – the annual motor vehicle production in the Czech Republic exceeded 1.4 million in 2023. Slovakia produces the largest number of motor vehicles relative to the size of population.

Since 2004, total stock of both private and public capital in EU-8 had expanded at a much faster rate than in other EU countries. Especially impressive gains were recorded in the Baltic States and Poland. An important case in point is the automotive industry in Eastern Europe. The Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia received both brownfield and greenfield investments from leading carmakers such as Audi, BMW, Citroen, Jaguar, Land Rover, Kia, Mercedes, Peugeot, Renault, Toyota Motors, and Volkswagen. The Czech Republic and Slovakia, especially, became automotive industry hubs – the annual motor vehicle production in the Czech Republic exceeded 1.4 million in 2023. Slovakia produces the largest number of motor vehicles relative to the size of population.

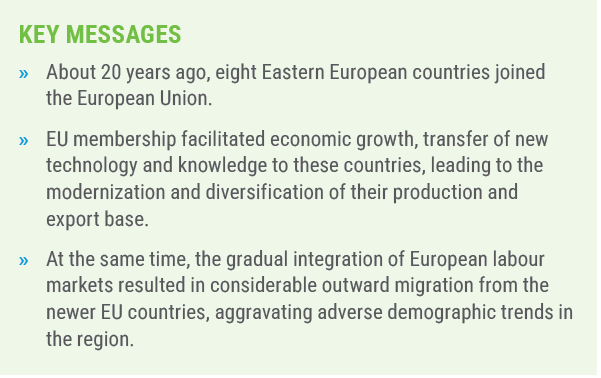

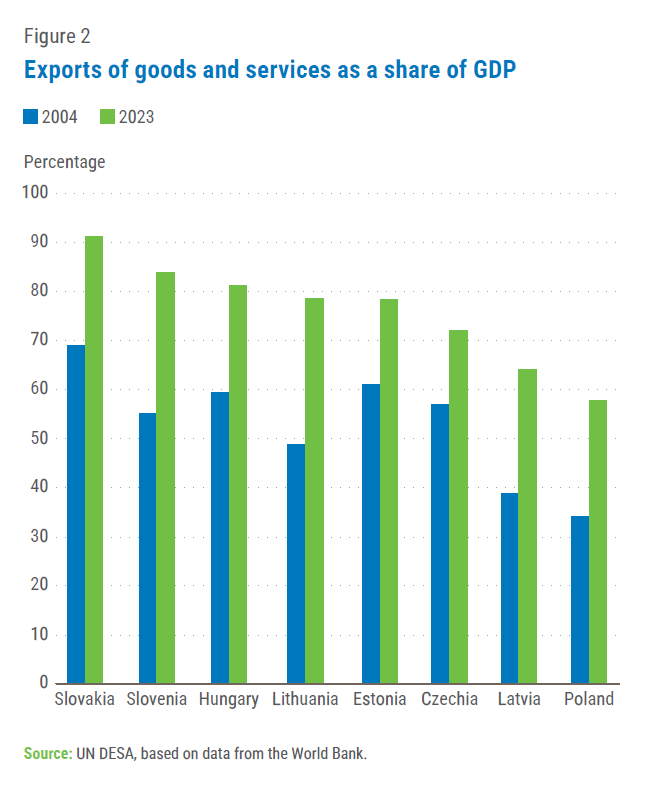

One of the important pillars of the EU accession “bonus” for the newer members was the deep integration into the EU’s single market for goods and services, underpinned by a strong growth in exports as a share of GDP. Geographical proximity and infrastructure connections played an important role in this integration, along with historical and cultural factors. Denmark, Finland and Sweden became important destinations for exports from Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Germany became the major export market for the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Slovakia and Slovenia. The EU-8 economies have the largest export-to-GDP ratios in the EU, averaging more than 60 per cent and exceeding 90 per cent for Slovakia (figure 2). Although the share of domestic value-added in total exports initially declined in most EU-8 countries, reflecting high import contents of exports, gradual technological upgrade and diversification reversed this trend, as the patterns of FDI also changed towards more knowledge-intensive sectors. Over the 20 years of EU membership, technological sophistication and knowledge-intensity of Eastern European exports has noticeably improved (figure 3). Machinery and transport equipment, including cars and other road vehicles, comprises the bulk of those exports, along with electrical and electronic goods. The fuel refining industry is important for external trade of the Baltic States.

The financial sector of Eastern Europe also attracted significant investment flows, with major Western banks moving to the region, including Raiffeisen, Société Générale, Swedbank, UniCredit, and others. The share of foreign ownership of Eastern European banks, except for Slovenia, became extremely high, varying from 80 per cent in Poland to almost 100 per cent in Estonia. While these investments alleviated local households’ and businesses’ financial constraints, they also led to an unprecedented rise in household debt, especially housing debt.

Very importantly, EU’s financial assistance to the newly admitted countries was massive. Even prior to the accession, those countries benefitted from several important EU financing instruments. Since joining the EU, the newer EU members received financial assistance, amounting to hundreds of billions of euros, paid from the EU funds. Assistance through the payments from the Common Agricultural Policy, Structural and Investment Funds, including the Cohesion Fund, helped the countries to narrow the economic gap with older EU member states and upgrade physical infrastructure and quality of governance.

Integration of labour markets and migration flows

Integration of labour markets and migration flows

Compared with goods, services and capital, labour in the EU has been comparatively immobile. Prior to the enlargement in 2004, despite the absence of formal barriers to labour mobility, only around 3 per cent of EU citizens lived in another country. Nevertheless, significant wage differentials with Western Europe and high unemployment in the EU-8 cased serious concerns about the possible large migration wave from the East. Only Ireland, Sweden and the United Kingdom (then a member of the EU) immediately opened their labour markets for the citizens of new member states. Other Western European countries requested derogations, introducing transitional periods for up to seven years in total. Consequently, while prior to the EU enlargement Austria and Germany were the top destinations for migrant workers from the EU-8, after 2004 around 70 per cent of migrants went to Ireland and the United Kingdom.

However, outward migration aggravated adverse demographic trends, especially in the Baltic States (figure 4). The demographic situation in the EU-8 was unfavourable since the 1990s due to the collapsing fertility rates and lower life expectancy than in Western Europe. Since 2004, over 744,000 people left Lithuania and moved mostly to other EU countries; over 2 million Polish citizens moved abroad. Shrinking population and higher dependency ratios cause labour shortages and weigh on budgets. The recent influx of Ukrainian refugees, along with immigration from Western Balkan countries, has somewhat alleviated labour shortages in education, healthcare, and social services sectors, however, it may not be a permanent solution. Against such background, it is worrisome that despite the currently historically low unemployment rates in EU-8, the level of youth unemployment and the share of young people neither in employment, education or training (NEET) still remains high in the region, approaching 15 per cent. Public opinion surveys show that over 20 per cent of young people in Eastern Europe desire to emigrate. Migration of youth and especially highly educated workers may cause a “brain drain”, curbing technological innovation. To prevent these developments, EU-8 countries should expand vocational training programmes and policies to reduce youth unemployment.

Further convergence prospects

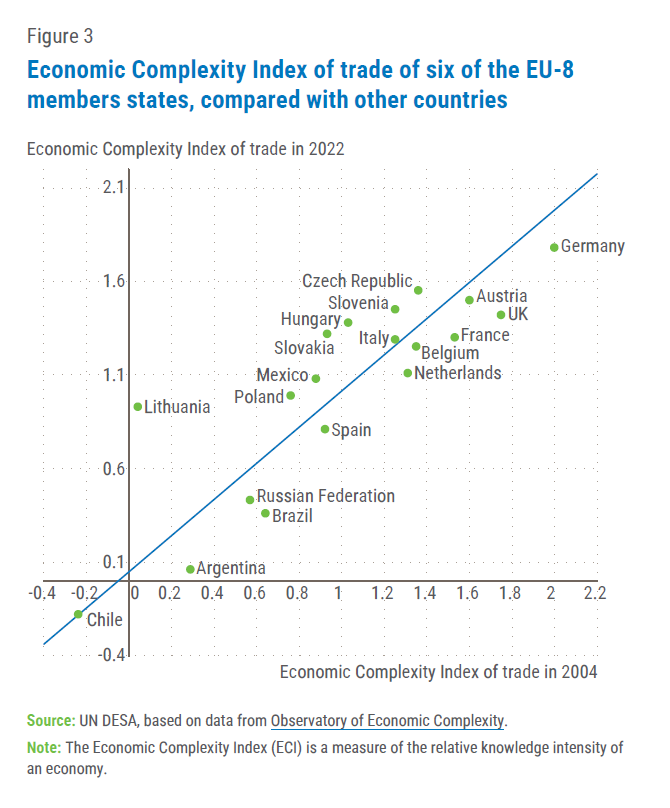

Two decades of EU membership had very notable effects on the economies of the newly admitted member states. However, the goal of converging towards the Western European living standards in the region is not accomplished yet. In 2023, for example, average hourly wages in all EU-8 states stood well below the EU average, especially in Hungary, Poland, and Lithuania. To remain on convergence track, per capita output in Eastern European countries should continue to grow at a faster rate, compared with their Western peers. However, with strained domestic labour markets, high employment rates, and unfavourable demographic outlook, additional growth is unlikely to be generated by increase in the total working hours. Instead, growth should be generated by further gains in productivity per hour worked. There are, however, signs that productivity growth in many Eastern European countries is slowing (figure 5a and 5b).

Two decades of EU membership had very notable effects on the economies of the newly admitted member states. However, the goal of converging towards the Western European living standards in the region is not accomplished yet. In 2023, for example, average hourly wages in all EU-8 states stood well below the EU average, especially in Hungary, Poland, and Lithuania. To remain on convergence track, per capita output in Eastern European countries should continue to grow at a faster rate, compared with their Western peers. However, with strained domestic labour markets, high employment rates, and unfavourable demographic outlook, additional growth is unlikely to be generated by increase in the total working hours. Instead, growth should be generated by further gains in productivity per hour worked. There are, however, signs that productivity growth in many Eastern European countries is slowing (figure 5a and 5b).

The initial competitive edge of Eastern European countries – lower cost of labour and other inputs – has been constantly eroding over time, especially for the Czech Republic and Poland (figure 6), and any further gains from being a cheap manufacturing location for Western companies may be elusive. Five of the EU-8 countries are currently members of the euro area, which implies that competitiveness cannot be boosted through exchange rate policy. Persistent labour shortages driving up nominal wages rule out policies of the so-called “internal devaluation” – reductions in labour costs. Meanwhile, energy intensity of GDP in the EU-8 countries is much higher than in Western Europe, which became a more important factor since the beginning of the war in Ukraine in 2022 and sharp reduction of Russian hydrocarbon imports to Europe.

To close the output gap with Western Europe, new drivers of productivity growth, and new areas of investment must be found. Economic policy in the region should aim to increase investments in research and development and on human capital, develop more advanced, high-tech sectors, such as information technologies, including AI, biotech, and digital industries. Automation, including in the automotive industry may somewhat compensate for the shrinking population. Even after 20 years of EU membership, EU-8 economies are running trade surpluses in medium-tech and resource- and labour-intensive goods, while in the group of high-tech goods trade deficits are persistent. Innovation is crucial to raise the share of domestic value-adding in exports and to sustain a longer-term economic growth differential with Western Europe that would lead to convergence. Domestic economic policies should also encourage return of skilled migrants. In this regard, the ongoing fragmentation and reconfiguration of the global production chains, creates both challenges and opportunities for the EU-8 countries.

Development of new renewable energy sources, supported by EU funding from the multi-annual financial framework 2020–2027 and the NextGenerationEU Recovery Plan, may be another promising area for bolstering economic growth. Despite the noticeable progress in developing renewable energy sources and reducing emissions, EU-8 countries are lagging Western Europe in renewable energy generation. The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland are excessively reliant on fossil fuels, including coal. Advancing the green economy, apart from environmental benefits, will facilitate accomplishment of the convergence goal.

Development of new renewable energy sources, supported by EU funding from the multi-annual financial framework 2020–2027 and the NextGenerationEU Recovery Plan, may be another promising area for bolstering economic growth. Despite the noticeable progress in developing renewable energy sources and reducing emissions, EU-8 countries are lagging Western Europe in renewable energy generation. The Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland are excessively reliant on fossil fuels, including coal. Advancing the green economy, apart from environmental benefits, will facilitate accomplishment of the convergence goal.

Follow Us