World Economic Situation and Prospects: March 2023 Briefing, No. 170

Economic consequences of the lingering war in Ukraine

Economic consequences of the lingering war in Ukraine

After a year, the war in Ukraine is still raging, imposing a heavy human toll, causing a massive devastation in the conflict area, and posing a grave threat to global security. The economic impact of the war is reverberating worldwide, contributing to inflationary pressures, and impeding the post-pandemic recovery. The war led to elevated energy prices and exacerbated food shortages in many regions. The repercussions of the conflict are being felt both in developed economies, especially in Europe, which has been confronted with skyrocketing energy prices, threats to its energy security, and inflow of the Ukrainian refugees, and in developing countries, especially those with high shares of grains in their food consumption basket. Rising inflation over 2022 (where the Ukraine war was one of several contributing factors) eroded disposable incomes, while higher food prices and disruptions in grain exports led to increased incidences of food insecurity and hunger. Although some effects of the war have been mitigated by targeted policy measures and initiatives, including the UN-brokered Black Sea Grain Initiative, the ongoing conflict continues to pose significant challenges to global economic recovery and stability.

Global repercussions of the geopolitical crisis

Forfeited economic growth

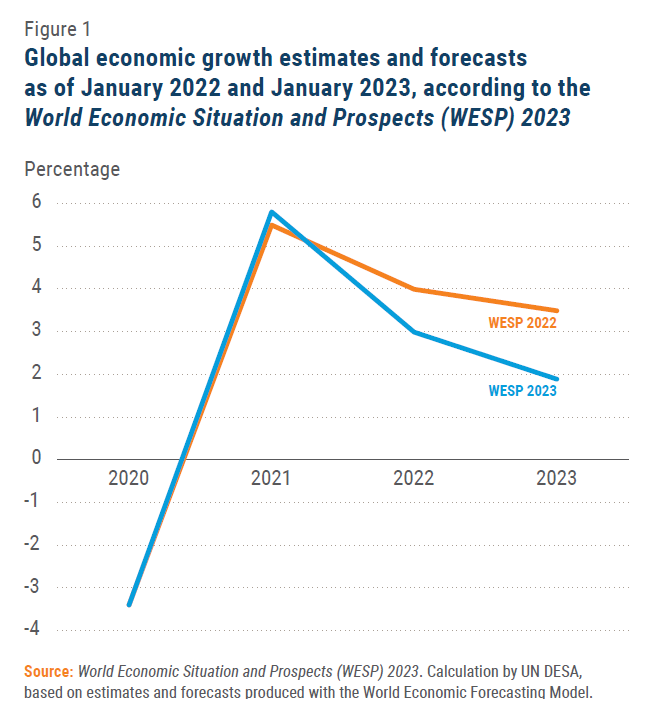

The war in Ukraine was not the sole factor behind the slower than anticipated economic growth in in most regions in 2022, and the less optimistic vision for 2023 (Figure 1). Extensive lockdowns in China and the concurrent supply-chain disruptions, unwinding of earlier fiscal stimuli both in developed and developing countries, along with the steeper-than-anticipated path of monetary tightening by the leading central banks impeded economic growth in 2022. However, the conflict was one of the main drivers of economic slowdown in the second half of 2022 in certain regions, including in Europe, as it disrupted supply routes and added to the already strong inflationary pressures, while economies – reopening after lockdowns and restrictions on mobility – were witnessing the release of pent-up demand. Disruptions in natural gas supply to Europe and the consequent surging gas and electricity prices hurt consumers and industries and led to energy rationing.

The war in Ukraine was not the sole factor behind the slower than anticipated economic growth in in most regions in 2022, and the less optimistic vision for 2023 (Figure 1). Extensive lockdowns in China and the concurrent supply-chain disruptions, unwinding of earlier fiscal stimuli both in developed and developing countries, along with the steeper-than-anticipated path of monetary tightening by the leading central banks impeded economic growth in 2022. However, the conflict was one of the main drivers of economic slowdown in the second half of 2022 in certain regions, including in Europe, as it disrupted supply routes and added to the already strong inflationary pressures, while economies – reopening after lockdowns and restrictions on mobility – were witnessing the release of pent-up demand. Disruptions in natural gas supply to Europe and the consequent surging gas and electricity prices hurt consumers and industries and led to energy rationing.

In many regions, inflation reached double-digit levels in 2022; thus, the conflict indirectly influenced monetary policy decisions. Although energy and commodity exporters have benefited somewhat from improved terms of trade in 2022, for many regions economic outcomes in 2022 was disappointing, with the weakness expected to persist at least until the first half of 2023. Many European countries, while succeeding in averting an energy crisis, may experience a moderate recession in early 2023.

Commodity and energy price dynamics

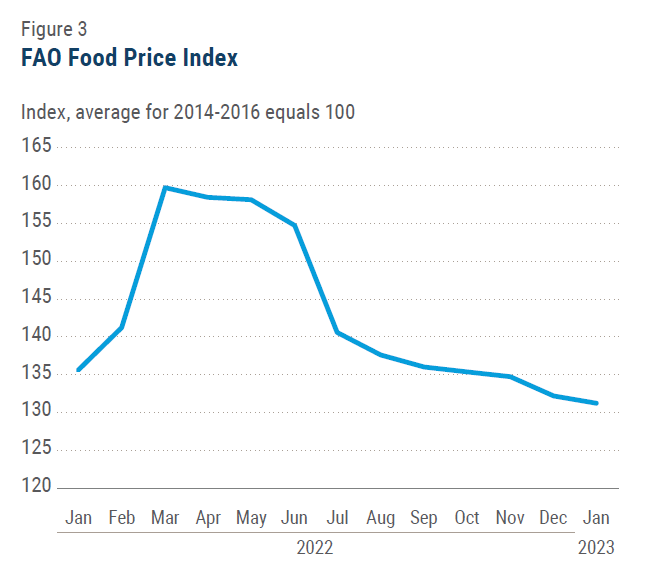

The conflict initially led to a pronounced rise in the prices of oil and natural gas (also driving up the price of coal), along with the prices of metals and grains, against the background of perceived delivery or even production disruptions (Figure 2). Difficulties over payment schemes and explosions at the Nord Stream 1 pipeline in September 2022 resulted in reduced flow of Russian natural gas to Europe. The EU, meanwhile, moved to reduce its dependence on imports of Russian gas, sharply increasing purchases of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from Algeria, Azerbaijan, Norway, and the UK; and increasing electricity generation from coal, solar and wind sources.

As Europe successfully filled its gas storage facilities, reduced gas consumption by around 15 per cent, and experienced a relatively mild winter, prices have subsided from their peaks and are likely to ease further in 2023, remaining nevertheless well above their historical averages. However, the opening of the Chinese economy and recovery in Asian demand, as well as restocking of underground storages in Europe in the second half of 2023 may again push prices up. In the United States, natural gas prices, while remaining much below the European levels, increased in response to higher global demand for LNG. Those developments have expedited the efforts of shifting away from fossil fuels to renewable energy, but the near-term use of coal and other “dirty” fuels has increased in 2022, contributing to increasing CO2 emissions.

Oil prices have also subsided towards the end of 2022. However, the OPEC+ group of countries decided to decrease their oil production by 2 million barrels per day since October 2022 until the end of 2023. In response to the oil embargo and price caps on oil and oil products imposed by G7, Australia and the EU, the Russian Federation decided to reduce its oil output by 500,000 barrels a day from March 2023. Oil prices are likely to be volatile in 2023. Global oil demand is expected to reach record high levels as Chinese demand recovers, but high inflation and monetary tightening may keep demand in the OECD area sluggish in the first half of the year.

Prices of metals, such as aluminium, cobalt, nickel, palladium, and titanium have also spiked, hurting automotive and electronics production. As Russian producers of industrial metals largely remained outside official sanctions, prices eventually subsided. Prices may increase again over the coming year due to any supply chain pressures or due to market volatility.

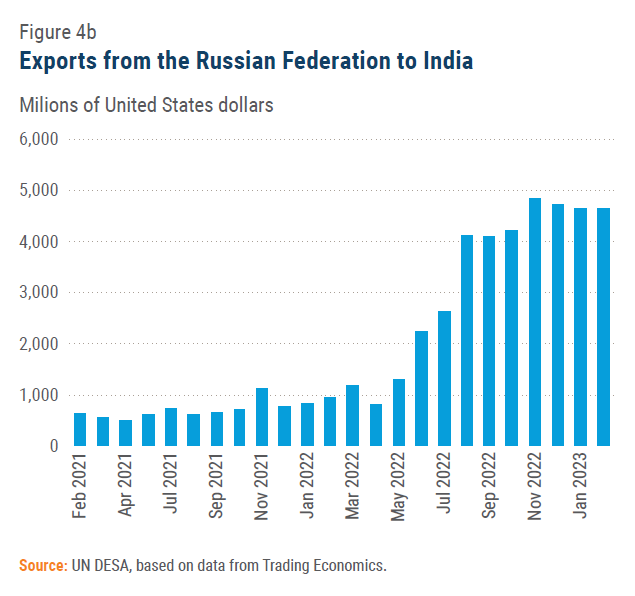

Since the Russian Federation and Ukraine are key global suppliers of agricultural goods, including corn, maize, fertilisers, and sunflower oil, supplying around 16 per cent of the world’s cereals, prices of these goods spiked since the outbreak of the war. Prices of other products, such as bread, meat, cooking oil, palm oil and other agricultural commodities have followed the trend. Thanks to the successful launch of the Black Sea Grain Initiative and grain and fertiliser exports out of three Ukrainian ports, as well as good harvests in other areas including Argentina, Australia, Brazil and Canada, grain prices retreated in the second half of 2022. Increasing exports of wheat from the Russian Federation contributed to the further price decline in January. Although the outlook is partly contingent on the continuation of the Black Sea Grain Initiative (set to expire on March 2023), and the reduced planting in Ukraine, global wheat supply appears to be at a satisfactory level, preventing large price shocks in 2023. The FAO Food Price Index (FFPI) has been falling from its March 2022 peak for ten consecutive months, further declining in January 2023 due to lower prices of vegetable oils, dairy and sugar (Figure 3).

Global food security situation

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine further exacerbated existing food shortages. According to the Update of the Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC) produced by the FAO, by mid-2022, the population facing the three highest phases of acute food insecurity was greater than at any point in the six-year history of the Report; up to 205 million people in 45 countries (among them 33 in Africa, 9 in Asia, 2 in Latin America and the Caribbean, and one in Europe) were facing acute food insecurity as those countries were in need of urgent external assistance for food. If figures for 2021 for those 8 countries/territories monitored by GRFC, where 2022 data was not available (such as Palestine or Syrian Arab Republic) are added, the total number would reach up to 222 million people in 53 countries/territories. Net importers of agricultural products, especially from the Black Sea region, became especially vulnerable (Bangladesh, Egypt, Pakistan, Türkiye, and Yemen are among the world’s top ten importers of wheat from both the Russian Federation and Ukraine; Lebanon is the ninth biggest importer of wheat from Ukraine).

The ongoing conflict in Ukraine further exacerbated existing food shortages. According to the Update of the Global Report on Food Crises (GRFC) produced by the FAO, by mid-2022, the population facing the three highest phases of acute food insecurity was greater than at any point in the six-year history of the Report; up to 205 million people in 45 countries (among them 33 in Africa, 9 in Asia, 2 in Latin America and the Caribbean, and one in Europe) were facing acute food insecurity as those countries were in need of urgent external assistance for food. If figures for 2021 for those 8 countries/territories monitored by GRFC, where 2022 data was not available (such as Palestine or Syrian Arab Republic) are added, the total number would reach up to 222 million people in 53 countries/territories. Net importers of agricultural products, especially from the Black Sea region, became especially vulnerable (Bangladesh, Egypt, Pakistan, Türkiye, and Yemen are among the world’s top ten importers of wheat from both the Russian Federation and Ukraine; Lebanon is the ninth biggest importer of wheat from Ukraine).

The Black Sea Grain Initiative, brokered by the United Nations and Türkiye in July 2022, somewhat alleviated the shortage of grain supplies. As of mid-February 2023, a total of 21,411,838 tons of foodstuff was shipped out of Ukrainian ports, with corn comprising 47 per cent of total shipments, wheat 25 per cent and sunflower oil 5 per cent. As of mid-January, around 44 per cent of the wheat exported has been shipped to low and lower-middle income countries. The World Food Programme purchased 8 per cent of the total wheat exported under the Initiative in 2022 in support of its humanitarian operations. However, the process sharply slowed in January to February 2023, with other spillover effects from the war in Ukraine affecting farming prospects globally through recurrent shortages of fertilizers. Among other factors, fertilizer exports from the Russian Federation, while not subject to formal embargo, are encountering logistical hurdles.

Disruption in supply chains and fragmentation of the global economy

The war in Ukraine may have contributed to a reversal of the decades-long process of global economic integration with disruptions in the existing regional and global supply chains. Disruptions in maritime and railroads shipping and air traffic caused by the conflict, including passenger flights, affected international trade and tourism.

Estimates of the cost of economic fragmentation vary widely. According to IMF scenarios, the longer-term cost of trade fragmentation alone could range from 0.2 per cent to almost 7 per cent of global GDP. Factors influencing these estimates include reduced global trade flows, technological decoupling, sectoral misallocation, lower diffusion of innovations and slower productivity growth. Alternative payment systems, if developed to mitigate the risk of potential economic sanctions, would increase transaction costs for businesses. Fragmentation would also undermine diversification of production and export bases, reducing economic efficiencies and potentially reducing resilience.

Accommodating refugees and displaced persons

The conflict has triggered a massive flow of refugees from Ukraine to neighbouring countries. Since the beginning of the war, almost 8 million people, mostly women, children, and the elderly, have left the country with Hungary, Republic of Moldova, Poland, Romania, the Russian Federation, Slovakia, and to a lesser extent, Belarus, seeing an influx of Ukrainian refugees in need of support. The refugee inflow imposed a considerable financial burden, especially in border towns and at the regional level. Initial assessments placed the costs of accommodating and integrating Ukrainian refugees as around $30 billion globally.

According to UNHCR, as of 23 February 2023, almost 5 million people from Ukraine are currently registered for the EU’s Temporary Protection or similar national protection schemes in Europe (Table 1). Many of the refugees remain in Eastern Europe, in particular in Poland, where a large Ukrainian diaspora had already formed in previous years.

According to UNHCR, as of 23 February 2023, almost 5 million people from Ukraine are currently registered for the EU’s Temporary Protection or similar national protection schemes in Europe (Table 1). Many of the refugees remain in Eastern Europe, in particular in Poland, where a large Ukrainian diaspora had already formed in previous years.

While refugee influx is associated with increased public expenditures initially and may lead to increases in property and rental prices, there is also a boost to the local economy. More importantly, such an influx may also offset depopulation trends and severe labour shortages in many countries, notwithstanding possible skill mismatches. The European continent is facing a serious problem of shrinking labour force and ageing population, with the situation especially grave in Bulgaria, Latvia and Romania, where low birth rates are combined with a low immigration. The influx of people from Ukraine helped to fill vacant positions in different sectors. Overall, there is evidence of active integration of majority of Ukrainians who have recently moved to Europe, especially in Eastern European countries.

Impact of the war on the CIS region and Eastern Europe

Surprisingly mild contraction of the Russian economy in 2022, but highly uncertain economic future

Since the outbreak of the war in Ukraine, many developed countries introduced economic sanctions against the Russian Federation, with the aim to curtail the country’s economic links with the rest of the world. Numerous restrictions were imposed on key industrial sectors, prohibiting imports of materials and technologies, especially “dual-use” technologies and products, including semiconductors. Sanctions targeted the Central Bank of the Russian Federation, effectively freezing its overseas assets, and the Russian sovereign debt. A large share of the “security cushion” built up over many years became out of reach for the Russian authorities. The SWIFT messaging system severed connections with several major Russian banks. Since late February 2022, various sectors of the Russian economy experienced an exodus of foreign companies. Partial embargoes on Russian hydrocarbon exports were also introduced. The EU announced an embargo on Russian seaborne crude oil since early December 2022, extended to refined oil products since February 2023, and has been progressively reducing its reliance on Russian natural gas.

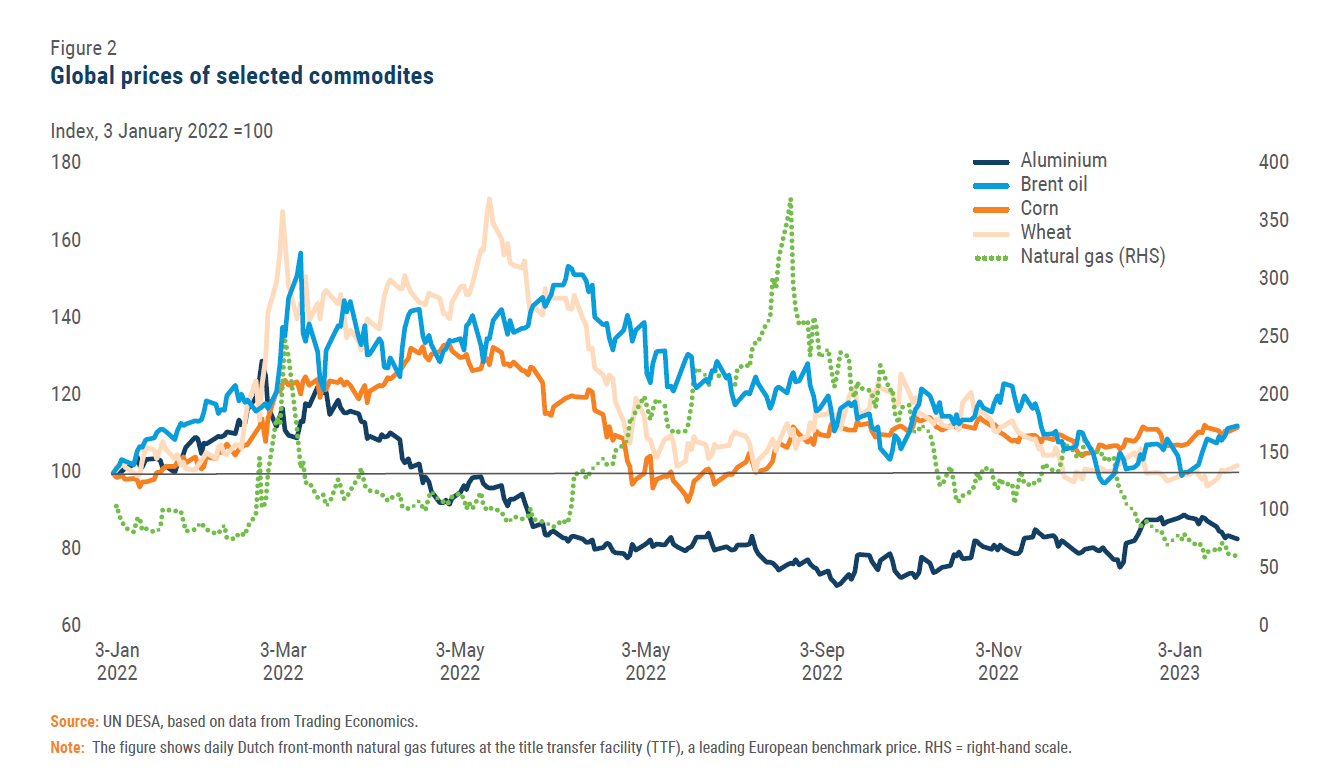

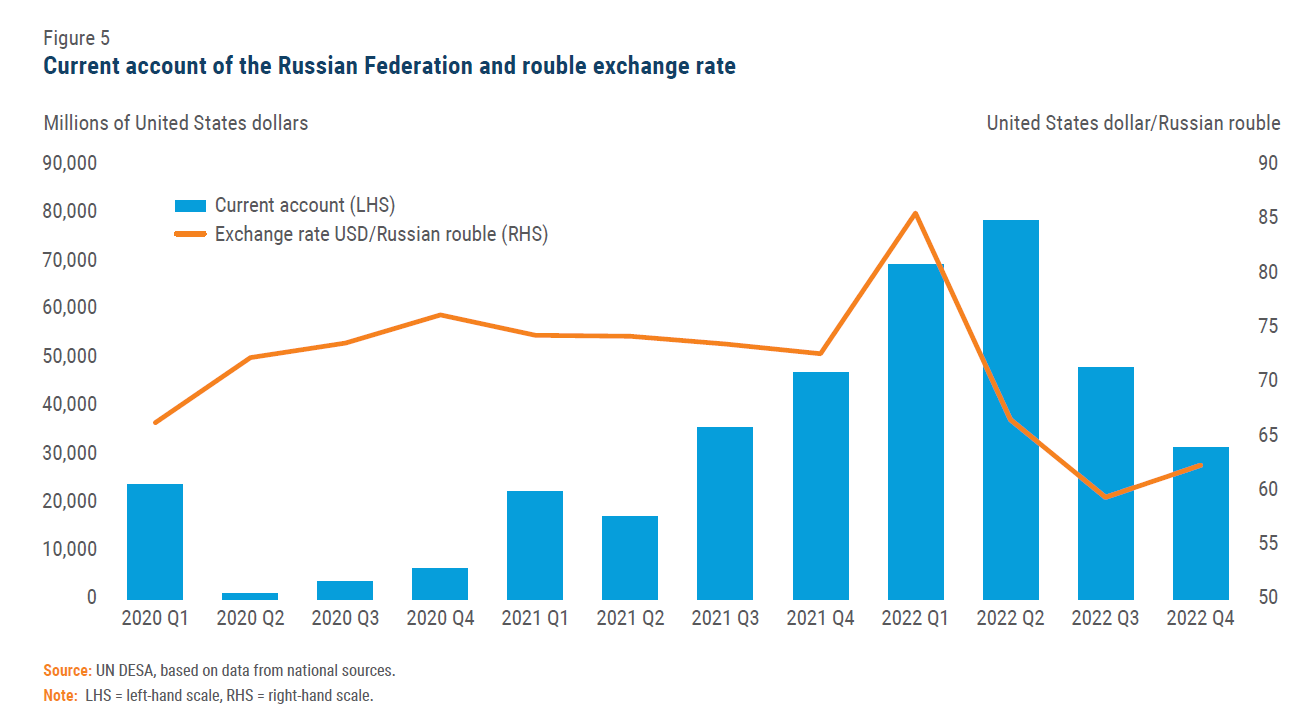

Most of the economic forecasts made in early 2022 predicted an 8 to 10 per cent annual contraction in the Russian GDP. However, according to the preliminary estimates, released by ROSSTAT on 20 February 2023, the decline stood at 2.1 per cent. High inventory levels of raw materials and foreign intermediate inputs, pre-stocked amid the pandemic-related supply chain disruptions, allowed many Russian companies to sustain production for some months. Despite the partial embargo against the purchase of Russian crude oil, export earnings remained strong as the directions of Russian exports have changed markedly, with increasing trade with China (Figure 4a), India (Figure 4b) and Türkiye, albeit at a discounted oil price. Although the flow of natural gas to Europe has declined, its prices have risen significantly. Imports meanwhile fell sharply due to the sanctions, disconnection from the SWIFT system, importers’ limited access to foreign currency and other factors. All told, the current account surplus reached a record high level in 2022, almost doubling compared to 2021 (Figure 5).

Since February 2022, the Central Bank of the Russian Federation has taken actions to preserve financial and currency stability. It sharply raised its policy rate and introduced capital controls. This prevented the outflow of liquidity from the banking system. The strong appreciation of the Russian currency since the second quarter, explained by the massive current account surplus. generated by high energy prices, import suppression, capital controls, conversion of European gas payments into roubles and the requirement for exporters to sell foreign exchange, contributed to stabilizing inflation, preventing a sharp fall in disposable incomes, and sustaining consumer demand. These developments made possible to reverse initial monetary tightening and restore corporate and retail lending. The increase in military spending also contributed to statistically increase the Russian GDP.

However, the outlook for the Russian economy deteriorated in late 2022, as the partial military mobilization in September contributed to the loss of human capital, including through outward migration. Some estimates suggest that the labour market lost about 1 million to 1.5 million people, with up to a third of Russian industry possibly facing labour shortages which could lead to wage and inflationary pressures, preventing further monetary easing.

However, the outlook for the Russian economy deteriorated in late 2022, as the partial military mobilization in September contributed to the loss of human capital, including through outward migration. Some estimates suggest that the labour market lost about 1 million to 1.5 million people, with up to a third of Russian industry possibly facing labour shortages which could lead to wage and inflationary pressures, preventing further monetary easing.

In early December 2022, the G7 countries, Australia, and the EU imposed a $60 per barrel price cap on Russian crude oil, prohibiting insurance and shipping services for vessels carrying Russian crude oil to third countries if price exceeds the cap. A similar embargo and price cap have been imposed on Russian petroleum products since early February 2023. As supply of Russian crude oil by tankers to the EU is no longer possible, China and India became the major purchasers of Russian crude oil, sold on a discount of up to $35 a barrel. Finding alternative to Europe markets for diesel fuel will be more difficult, as many potential buyers prefer their own oil refining. Nevertheless, since late 2022, the Russian Federation gradually rerouted its diesel exports away from the EU, with increasing sales to North Africa and Türkiye. Russian production of both crude oil and petroleum products are likely to decrease in 2023, and a repetition of large export earnings in 2023 is unlikely.

The Russian Federation may aim to build new supply chains, especially within the Eurasian Economic Union, as well as localize production cycles. However, the possible secondary sanctions would be a disincentive for other participants. The so-called “parallel import” schemes, while successfully addressing gaps in the consumer market (for example, for cars and electronics), can only partially support industrial activity, especially since unauthorized import does not ensure product quality.

The outlook for the Russian economy in 2023 is uncertain. As fiscal support to the economy is likely to be weaker, a shortage of workers will persist, and oil production is likely to decline, a further contraction by 2.5 to 3 per cent in 2023 is possible.

Massive (and expensive) reconstruction efforts will be needed in Ukraine

Massive (and expensive) reconstruction efforts will be needed in Ukraine

The economy of Ukraine in 2022 suffered massive destruction of its physical infrastructure, including railway and road links with neighbouring countries. According to the preliminary estimate from national sources, Ukraine’s economy contracted by about 30 per cent in 2022. A deeper economic downturn was prevented with the relocation of some enterprises to the relatively safer west of the country. Meanwhile, the financial infrastructure of Ukraine remained functional, with most banks continuing their activities, and the information technology sector – an essential source of foreign exchange earnings – performed well, with its exports increasing. However, the country’s public revenues fell sharply, and the increased military spending and support to the population have led to large budget and current account deficits.

Since the start of the war, Ukraine received extensive financial support from the EU, the United States, the International Monetary Fund, and the World Bank. The total amount of aid already committed or promised, including military assistance, is estimated at approximately $120 billion. In 2023, the EU will provide Ukraine with 18 billion euros in economic support, largely as loans (public debt, excluding contingent liabilities of State-owned enterprises, may reach 90 per cent of GDP in 2023). Direct financing from the National Bank of Ukraine covered about one third of total government spending requirements in 2022, which led to the depletion of foreign exchange reserves and currency devaluation. Ukraine has been granted a two-year suspension of Eurobond payments, but this will save only about $6 billion, close to estimated monthly budget shortfall. In May 2022, the EU suspended tariffs and quotas on imports from Ukraine, including agricultural and food imports, for one year. In December, the IMF approved a four-month Program Monitoring with Board Involvement (PMB) for Ukraine, to help the authorities implement prudent macroeconomic policies.

The resumption of grain exports under the Black Sea Grain Initiative and an increase in external financing slightly improved the country’s outlook in late 2022. Still, the prospects for the Ukrainian economy in 2023 and 2024 are highly uncertain and will depend on many factors, including the cessation of hostilities and the launch of reconstruction efforts. Post-conflict reconstruction of Ukraine will require tremendous resources, estimated at around $350 billion to $600 billion, and is likely to last many years.

Spill-over impact of the conflict on the CIS and Eastern Europe though trade, investment, and remittances

Most of the Eastern European countries close to the conflict area remained resilient in the first half of 2022. But skyrocketing inflation and sharp monetary tightening, along with elevated energy prices, led to a marked slowdown in economic activity toward the end of the year. In 2023, those economies, which are three times more energy-intensive than most of the Western European economies, are likely to see GDP growth in the range of just 1-2 per cent.

The Russian economy has a major impact on other CIS economies, through trade, investment, migration, and official financial support channels, and initially downbeat expectations in CIS countries prevailed.

However, individual country outcomes in the region showed significant variation. The economy of Belarus has contracted by over 4 per cent in 2022 as the country’s exports, including fertilizers, faced various restrictions over the year due to the war in Ukraine, disrupted supply routes through Europe, and sanctions. The Republic of Moldova received a large number of Ukrainian refugees, at least as the country of first entry, and experienced sharp reduction in Russian natural gas supplies and recurrent power outages being connected to Ukraine’s electricity grid. The country’s economy also contracted in 2022 and is likely to stagnate in the near term.

Some other economies, however, performed significantly better than expected, amid relocation of people and some businesses from the Russian Federation since February 2022. Money transfers from the Russian Federation to those countries sharply increased. Armenia and Georgia (not a CIS member) experienced double-digit growth in 2022. On the flipside, surging housing prices and rental costs have exacerbated social inequality. Exports to the Russian Federation, including re-exports, have increased, amid higher use of national currencies in settlements, and increased opportunities to fill gaps in the Russian consumer market. Energy exporters, such as Azerbaijan and Kazakhstan, have benefited from higher oil and natural gas prices. However, the observed trend of capital inflows may also be volatile and pose risks. The resulting appreciation of exchange rates has undermined exports to countries outside the CIS and currency fluctuations are detrimental for businesses.

Follow Us