On 26 June 1945, official representatives of 50 countries, meeting in San Francisco, United States, signed the Charter of the United Nations, forming the world’s premier international organization, dedicated to “saving succeeding generations from the scourge of war”. Eight decades after that day, the United Nations counts 193 Member States and works through a broad system of related agencies, funds and programmes to achieve, for all peoples, “peace, dignity and equality on a healthy planet”.

On 24 June 1947, in time for the second anniversary of the Charter, the United Nations Weekly Bulletin, which eventually became today’s UN Chronicle, published an article setting out the major events and historical context of the formation of the United Nations and the signing of its founding document. The article offers the truly unique and hopeful perspective of the Organization in its earliest days, setting out its purpose and promise, which remain remarkably relevant today.

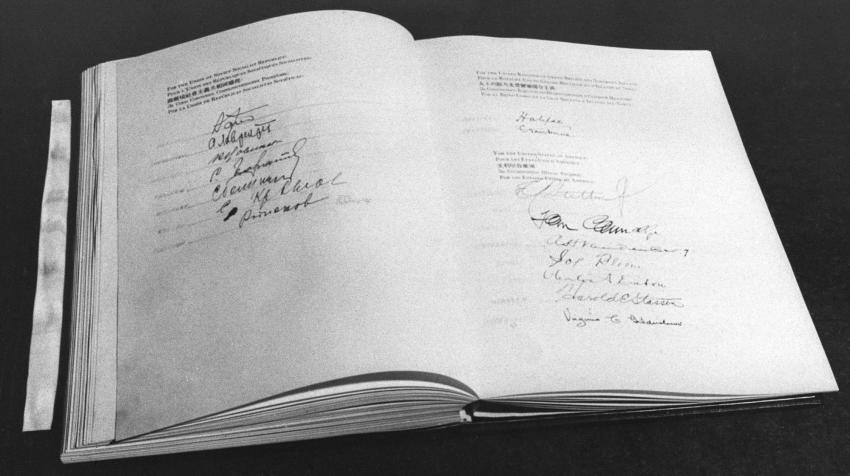

In honour of the eightieth anniversary of the signing of the Charter of the United Nations, the UN Chronicle is proud to republish below “The Story of the Charter” unedited, complete with original and contemporary photographs.

ON JUNE 26, 1945, the peoples of the United Nations, through their representatives assembled in San Francisco, established a new world organization to advance the ideals for which they had fought the most tragic war in history.

In taking this momentous step, the freedom-loving peoples of the world affirmed that the spirit of co-operation and unity of purpose which alone had made the military victory possible must be maintained to meet the challenge of the peace.

This realization that the nations must remain united was the result neither of chance nor of sudden decision. Two world wars in one generation—wars which had enveloped every corner of the globe and involved every segment of mankind—had driven home one inescapable conclusion: that the peace and security for which men had vainly longed for centuries could be attained only through the continued partnership, and vigilance, of all the peoples of the world. With every year, weapons of destruction have been assuming terrifying potentiality, and a third world war would wipe out the basis of civilization. Behind the signing of the United Nations Charter is the story of mankind's age-old attempts to take common action so that peace and security may be achieved. Some of the world's most illustrious poets and philosophers have outlined plans for a workable federation of nations. In 1313 Dante advocated a European union under a single benevolent ruler. In 1713 the Abbé St. Pierre argued on behalf of a perpetual alliance of European states and the use of compulsory arbitration to settle disputes. Jeremy Bentham advocated the reduction of armaments and the establishment of a "common legislature," while Immanuel Kant favored a general federation of states that should be universal in scope and that should embrace all the peoples of the world.

The first formal action of the Allied nations to work together for the preservation of peace was the Inter-Allied Conference at St. James's Palace, London, on June 12, 1941.

Throughout the nineteenth century the peace movement grew rapidly, and by 1914 there were about 150 peace organizations in the world. During the First World War, many of these groups discussed the possibility of creating an international league after the end of hostilities. The British Government appointed a committee to work out a plan for a league of nations. Meanwhile, Woodrow Wilson and General Smuts had also been formulating ideas for an international peace organization. Out of these plans came a draft which, with certain changes, finally emerged as the Covenant of the League of Nations.

During the decade from 1920 to 1930, the League was chiefly successful in the non-political field. Work in public health, the efforts of the ILO to improve labor conditions, control of the drug traffic, and many other achievements testified to the League's contributions in eliminating social evils.

But the thirties were a decade of unchecked aggression, culminating in the outbreak of the Second World War in September 1939. The peace-loving democracies found themselves on the defensive on all fronts, and it was not until the Germans were turned back at Stalingrad in the summer of 1943 that the tide of victory began to flow in the direction of the Allied cause. But the very desperation of the Allies during the critical first years forced them to pool their manpower and resources to develop military and economic co-operation as never before. It was this spirit that contributed most to the development of the United Nations.

The first formal action of the Allied nations to work together for the preservation of peace was the Inter-Allied Conference at St. James's Palace, London, on June 12, 1941. Here the representatives of Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czechoslovakia, France, Greece, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, the Union of South Africa, the United Kingdom, and Yugoslavia formally vowed to fight on until victory was won, and to work in unison with other free peoples for an enduring peace.

The Atlantic Charter

In August 1941, while the enemy was advancing in Russia and in southeastern Europe, and the Battle of the Atlantic was raging furiously, news came that President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill were in conference "somewhere at sea," and on August 14 the two leaders issued a joint declaration, known as the Atlantic Charter.

This declaration was not a formal treaty between two powers, nor yet a final expression of peace aims. It simply made known "certain common principles in the national policies of their respective countries on which they base their hopes for a better future for the world."

The Atlantic Charter declared that its signatories sought no aggrandizement of any kind and no territorial changes not in accord with the freely expressed wishes of the people concerned. They respected the right of all peoples to choose their own form of government, and they desired that all nations should have equal access to the trade and raw materials of the world. They desired the fullest collaboration between all nations in the economic field in order to attain improved labor standards and social security for all.

The sixth and eighth points in the Atlantic Charter related directly to world organization. "After the final destruction of Nazi tyranny," reads the sixth clause, "they hope to see established a peace which will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safety within their own boundaries, and which will afford assurance that all the men in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom from fear and want."

The eighth clause states that realistic and spiritual reasons alike necessitate the abandonment of the use of force. The Charter's authors looked forward to the establishment of "a wider and permanent system of general security." Pending such action, they called for the disarmament of aggressor nations and the use of practicable measures to lighten for peace-loving peoples the crushing burden of armaments.

The Atlantic Charter had expressed the principles and aspirations of the Allied peoples, and, coming as it did in the darkest days of the war, it gave hope and encouragement to all peace-loving peoples. But the Charter was more than a message of hope. It committed the signatory states to setting up an international organization, and the principles which it had stressed were further developed at every major Allied conference concerned with the problem of war and peace.

Declaration by United Nations

The second link in the chain of events leading to the signing of the Charter at San Francisco was forged on January 1, 1942, at Washington, D.C. The United States had just been attacked at Pearl Harbor, and representatives of 26 states at war with one or more of the Axis powers gathered at the White House.

There they signed the Declaration by United Nations—the first time when that historic phrase was used. The Declaration "subscribed to a common program of purposes and principles embodied in the joint declaration" known as the Atlantic Charter. In addition to accepting these principles, the 26 nations pledged themselves to use all their resources, both military and economic, to defeat the Axis, and they promised not to make a separate armistice or peace with the Axis powers.

It was provided that other nations which rendered assistance "in the struggle for victory over Hitlerism" might also adhere to the Declaration. By April 1945, when the San Francisco Conference opened, the number had grown to 47 states.

The months that followed the signing of the Declaration found the United Nations fighting on the Russian front, in the Mediterranean, and in the Pacific and the Far East. Much suffering and anxiety had to be endured before the British defeated Rommel at El Alamein in August 1942, before the Russians scored their victory at Stalingrad in January 1943, and before the Americans began to push the Japanese back from their island-held positions in 1943 and 1944. Yet, through all this period, constructive work for postwar international organization went ahead.

Moscow, Cairo, Teheran

Of particular significance for the United Nations were three conferences held in the closing months of 1943. The first conference met in Moscow in October, and was attended by the foreign ministers of the United States, the United Kingdom, the U.S.S.R., and China. The declaration which they issued stated in part:

"That they recognize the necessity of establishing at the earliest practicable date a general international organization, based on the principle of the sovereign equality of all peace-loving States, and open to membership by all such States, large and small, for the maintenance of international peace and security."

The organization, it was suggested, should be based on the principle of sovereign equality of all peace-loving states.

This commitment was far from specific; it did little more than establish unity of purpose among the four participating nations in matters of peace as well as war. But this commitment to establish and maintain an enduring peace was carried a step further at the Cairo and Teheran Conferences, held in December 1943.

The Cairo Declaration, issued by President Roosevelt, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek, and Prime Minister Churchill, proclaimed plans for bringing about the "unconditional surrender" of Japan. The Teheran Declaration bound the heads of the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union to work for an "enduring peace."

"With our diplomatic advisers," the Teheran Declaration said, "we have surveyed the problems of the future. We shall seek the cooperation and active participation of all nations, large and small, whose peoples in heart and in mind are dedicated, as are our own peoples, to the elimination of tyranny and slavery, oppression and intolerance. We will welcome them as they may choose to come into the world family of democratic nations."

Economic and Social Steps

The Moscow, Cairo, and Teheran Declarations represented a definite political commitment to work for an enduring peace. Meanwhile, action was being taken by the United Nations to cope with the economic and social problems which have been among the chief contributing factors to war.

Even through the years of wartime privation one thing was clear. Victory alone was not going to give mankind freedom from want—very far from it, for even in peace-time two thirds of the people of the world are undernourished. In May 1943 delegates from 44 countries participated in the Food and Agriculture Conference at Hot Springs, Virginia. The Conference decided that nations must act together to increase food production and improve distribution. They decided to set up a permanent agency to carry through this program, the Food and Agriculture Organization, which came into being in October 1945.

Every war is accompanied by economic and social dislocation, and, long before the Second World War drew to a close, the United Nations began planning to meet the problems of post-military relief and rehabilitation. On November 9, 1943, representatives of 44 nations signed at the White House the agreement bringing into existence the first international organization to be created by the United Nations—UNRRA.

The United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration was established as a temporary agency with a special job to perform: to help the victims of aggression to help themselves. This assistance was of two sorts: short-term aid in the form of food, clothing, medical supplies, and health and welfare services; longer-term aid through the agricultural and industrial rehabilitation of shattered economies. In addition, UNRRA was established to assist the military authorities in caring for the millions of persons displaced by the war.

With UNRRA set up to handle relief and rehabilitation, the United Nations turned its attention to problems connected with permanent reconstruction and the development of world economy. Another important United Nations Conference was held, this time at Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, in July 1944. The 44 nations at the Conference adopted plans calling for the creation of an International Monetary Fund to stabilize currencies and so promote the flow of foreign trade. They also recommended the creation of an International Bank for Reconstruction and Development to provide facilities for long-term loans. With such loans, a country could undertake long-term programs of reconstruction or industrialization, designed to raise its standard of living.

Dumbarton Oaks

In the month following the Bretton Woods Conference, the representatives of the U.S.S.R., the United States, and the United Kingdom (joined later by the representative of China) met in Washington, D.C., to hold the now-famous Dumbarton Oaks conversations. The people of the United States and of other countries took an intense interest in these conversations, so that "Dumbarton Oaks" became literally a household word during the winter of 1944-45.

The unprecedented interest in this Conference was not hard to understand. The conversations were concerned directly with the establishment of an international organization for the maintenance of peace and security—and upon the success or failure of these conversations hinged the whole postwar history of the United Nations.

On October 9 the results of these conversations were published as the Dumbarton Oaks Proposals. As Secretary of State Cordell Hull said, they were made available "for full study and discussion by the people of all countries." They were literally "Proposals." Not complete or final, the Proposals only suggested a blueprint for an international organization, to be known as "The United Nations," for the purpose of maintaining international peace and security.

The organization, it was suggested, should be based on the principle of sovereign equality of all peace-loving states. It was to have as its principal organs a General Assembly, a Security Council, an International Court of Justice, and a Secretariat. The composition and functions of the Assembly and the Security Council were outlined. No proposals were made on the voting procedure in the Security Council. Other chapters of the Proposals were concerned with arrangements for maintaining peace and security, including the prevention and suppression of aggression; arrangements for international economic and social co-operation, including provisions for an Economic and Social Council; and transitional arrangements.

These Proposals represented the degree of agreement which the representatives of the four great powers had been able to reach, and the peoples of the United Nations realized that they must serve as the general basis for the new international organization.

No attempt was made at Dumbarton Oaks to draft the statute of an international court. Such a court had been agreed upon, but no decision was reached whether it should be a new court or the old Permanent Court of International Justice with its Statute revised. Between Dumbarton Oaks and the calling of the San Francisco Conference, invitations were sent out to those countries which had adhered to the Declaration by United Nations to send representatives to a meeting in Washington to prepare a draft statute for the proposed court. The Committee of Jurists met in April and drafted a report for submission to the Conference.

Yalta

The last great step leading up to the calling of the United Nations Conference on International Organization was the issuance of a statement in February 1945 at Yalta, in the Crimea. Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill had met at this resort town to consider many important matters. After eight days of full discussion, they reported that "Nazi Germany is doomed" and that plans had been made for her occupation and control.

The three leaders also announced that a Conference of the United Nations was to be held at San Francisco on April 25 to prepare the Charter for the "general international organization" which the Moscow Conference had first forecast in October 1943. China and France were to be invited to join in sponsoring the Conference.

At Yalta the three national heads reached agreement on a problem which had vexed the delegates at Dumbarton Oaks. This was the question of the voting procedure in the Security Council. A voting formula was agreed on at the Yalta Conference, but it was announced that the plan would be made public only after consultations with China and France.

On April 12, Franklin Delano Roosevelt died, and the work which he had so greatly advanced was left to others to complete.

The decision reached at Yalta left only ten weeks of preparation before the Conference opened at San Francisco. During that time there occurred two significant events. One was the calling of the Inter-American Conference on Problems of War and Peace, which met at Mexico City from February 21 to March 8. The Conference, attended by representatives of all the American republics except Argentina, approved the Dumbarton Oaks Proposals in principle, while suggesting various changes and additions.

The second event was at once unexpected and tragic. The leader who had done so much to establish the United Nations did not live to see the Conference convened. On April 12, Franklin Delano Roosevelt died, and the work which he had so greatly advanced was left to others to complete. Notwithstanding this blow, it was decided to go ahead with the arrangements for the Conference. It was therefore in a spirit of dedication that the representatives of the United Nations met at San Francisco.

San Francisco

The Conference on International Organization met from April 25 to June 26. During those hectic two months, San Francisco played host to 850 delegates, plus their advisers and staff, who, together with the Conference secretariat, brought the total to 3,500. San Francisco also had the problem of taking care of the needs of more than 2,500 press, radio, and newsreel representatives from all over the world. In addition, scores of national and international organizations were represented unofficially at the Conference.

Of the 50 countries represented at the Conference, 46 were present at the opening, and delegates of the Ukrainian and Byelorussian Soviet Socialist Republics, Argentina, and Denmark were seated later, when they were admitted. Poland was a signatory of the United Nations Declaration, but its new government was not formed in time for it to be represented at the Conference.

Four principal commissions were set up to work out the details of the Charter: Commission I handled General Provisions; Commission II, the General Assembly; Commission III, the Security Council; and Commission IV, the Judicial Organization. Under each commission were committees, numbering twelve in all. Each country was represented on each of these commissions and committees, where the basic work of the Conference took place. Their decisions were later submitted to the plenary sessions for approval.

The Charter in its final form embodied many alterations and additions to the Dumbarton Oaks Proposals. A Preamble was added, as was a Declaration on Non-Self-Governing Territories, which went beyond any previous international agreement in recognizing the principle that "the interests of the inhabitants of these territories are paramount," and in making it obligatory to promote to the utmost, "as a sacred trust," the well-being of these peoples.

The Conference also created an International Trusteeship System to promote the development of the people concerned "toward self-government or independence," and established, as a major organ, a Trusteeship Council to perform various functions in the interest of the peoples of the Trust Territories.

To China, first victim of aggression by an Axis power, fell the honor of signing first. The other nations then followed until, at the end of a seven-hour ceremony, 153 signatures had been inscribed.

The Economic and Social Council was raised from a minor position to become one of the six major organs of the United Nations, and a strong emphasis was placed throughout the Charter on the economic and social advancement of all peoples. Methods of voting in the Security Council and of fitting regional systems of security into the United Nations were developed. The powers of the General Assembly were extended and its prestige raised to enable this body to function as a great world parliament. The Conference also drew up a statute for a new International Court of Justice.

On June 25, the Conference voted unanimously to adopt the Charter, and on the following day the signing of the historic document took place. The blue-leather-bound books were placed on an eleven-foot round table, while the silk flags of the 50 United Nations formed a colorful background. To China, first victim of aggression by an Axis power, fell the honor of signing first. The other nations then followed until, at the end of a seven-hour ceremony, 153 signatures had been inscribed. Two documents had to be signed, one containing the Charter and the Court Statute in the five official languages, and the other the agreement for the Preparatory Commission to set up the United Nations machinery.

The Conference closed with an address by President Truman, who flew to San Francisco for the occasion. Congratulating the representatives on their historic task, President Truman added these sober words:

"If we had had this Charter a few years ago—and, above all, the will to use it—millions now dead would be alive. If we should falter in the future in our will to use it, millions now living will surely die."

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.