27 January 2023

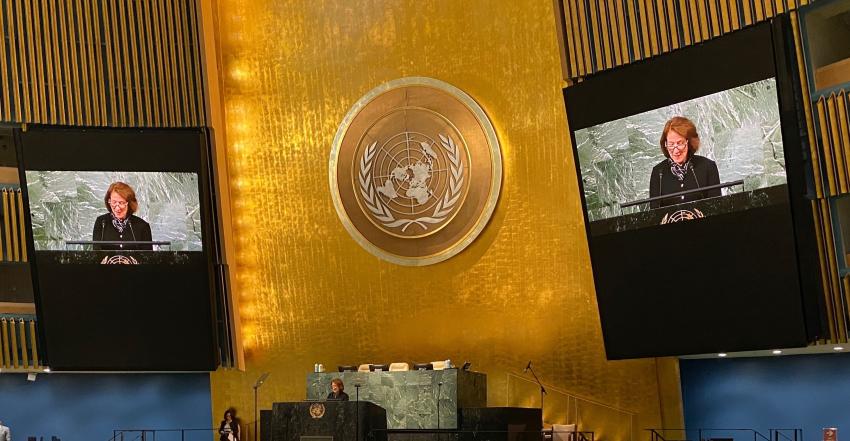

The United Nations Holocaust Memorial Ceremony marks the International Day of Commemoration in Memory of the Victims of the Holocaust. Held in the General Assembly Hall, this solemn occasion serves a vital role: it signals the significance of this genocide to the international community. This year, the Holocaust and the United Nations Outreach Programme will explore how victims adjusted their ideas of home and belonging. It is an all too relevant subject in a world with more than 100 million refugees and forcibly displaced persons. I am honored to have been invited to present the following remarks at the annual Memorial Ceremony on 27 January 2023.

When the Second World War ended, Maria Elsner and her mother and sister walked and jumped trains from Strasshof, Austria, where they had been slave laborers, to their hometown in Hungary. They were convinced that Mr. Elsner had survived. “Not only was Father not there, the whole house was totally empty”, Maria recalled. “No bed, no table, not a chair, nothing. . . That was our homecoming. . . We were there; Mother on the ruins of her life. We imagined that when we returned we would come back to our old lives. The old life never came back . . . And we had nothing.”1

Where and to whom did Holocaust survivors belong? Throughout the Nazi era, Jews preserved the hope that their families would be reunited. They presumed that when the Third Reich fell, the old structures and certainties would be restored. As they learned, they were wrong. They returned to naught. Their suffering did not end, it simply took a new form.

Maria Elsner returned expecting unification with her father. By the time Lena Jedwab returned to her native Poland, she held no such hope. Born in Bialystok, Lena joined the communist youth organization when the Soviets occupied her city in 1939. The German attack on the Soviet Union in June 1941 found her working as a counselor in a Young Pioneers summer camp, which was evacuated to the Autonomous Soviet Republic of Udmurtia. Her days, she confided in her diary, passed “in unending sorrow and yearning for home.” “Is home really a cot in a communal dormitory?”, she exclaimed. “No! My home is there—on the other side of the front, in Bialystok!”2

She adjusted, adapted, conformed. Yet she remained isolated. “Nobody worries about me, thinks about me,” she grieved in September 1943. “I will never ever have a home.”3

Lena wrote to her family in Bialystok immediately after the city was liberated. Devastating news came in return. “6 September 1944. The pain of waiting has ended with greater pain: all the many letters that I sent to Bialystok have been returned with the notation that the addressees are absent. The horror is clear: they all perished.” With nothing and no one awaiting her in her homeland, Lena remained in the Soviet Union until attacks against Jews prompted her to seek greater safety in Lodz. She did not find it, and she fled again. Crossing the Polish border clandestinely in August 1948, she made her way to Paris.4

Survivors faced financial challenges as well as emotional difficulties. The situation of Hanna-Ruth Klopstock, a German-Jewish child sent to safety in France, reflected the postwar economic conditions of many European Jews, conditions that militated against creating a home or sense of belonging. The sole survivor of her nuclear family, Hanna-Ruth remained in France after the war. Pregnant in 1946, she took a position in a Jewish orphanage to provide for her baby, Gisela. In 1954, Hanna-Ruth wrote: “Sadly, the conditions in which I find myself are not such as to make life easier. . . . Who would have thought [at Liberation] in 1944 that 1954 would be as it has turned out to be?” Housing was beyond her reach. She sublet a small room in an apartment.5 Two years later, Hanna-Ruth worked as a cook in a vocational school, forced to live apart from Gisela. “We still don’t have a home. She is in an orphanage near Paris.” Mother and daughter visited every Sunday.6

Hanna-Ruth’s predicament was not extraordinary. Of the 40,000 Jewish refugees in France in 1940, some 8,000 had survived the war in that country. Those of working age and older had absolutely nothing: no clothing, linens, personal possessions or housing. All who had flats or houses when the Germans invaded had been denied repossession in 1945 and, because of the chronic postwar housing shortage, the only accommodations they could obtain were hotel rooms, which typically absorbed half of their meager earnings. Then too, many refugees were aging, and marked by their experience of betrayal by the French State. They would not claim the relief to which they were entitled, fearing expulsion for living on public funds.7

Jews who had fled to Great Britain fared little better. They had been spared persecution. And, as most had been naturalized, their legal situation was stable. Yet their circumstances remained marginal. As a leader of the German-Jewish refugee community in Britain observed in 1955, “Even though the majority are employed, their income is not sufficient to allow them savings”. Whatever they had put by in Germany had been lost, and their wages in Britain had not afforded them the opportunity to recoup. “Only very few of them can think of retiring and they dread the day... when a breakdown in health would force them to give up their positions.”8 Like survivors everywhere, they had little family to turn to for help. Those basic networks of mutual assistance and care had been destroyed.

If older survivors had lost their professions, many younger people were disappointed by the post-war opportunities open to them. Marianka Zadikow’s history plots this story. Marianka and her parents were deported to Theresienstadt, where her father died; she and her mother lived to return to Prague. Family, Jewish community, national identity—all were destroyed. “I was very close to suicide in 1945. The war was ended. In Prague. Where you saw nothing but empty windows of people who were dead.”9

Marianka immigrated as a Displaced Person to the United States in 1947. She hoped for an education, but “I never had another chance for schooling.” She married; she had two daughters. Her family enriched her life. Still, “some of us know that under other circumstances we would have done better.” She and her husband had a chicken farm. “I had to do with nothing but chickens. For 17 years, no people, never.” After her husband died, Marianka, the person who had lit fires and cleaned toilets in Theresienstadt became a custodian in the public schools. “And the next 11 years, I had again no people because I was cleaning classrooms and bathrooms and throwing away garbage and having absolutely nothing to do with people.”

The history of Holocaust survivors resists a triumphalist conclusion. They survived, went on, made lives for themselves; and they lost their homes, language, families, roots, and sense of belonging. At the same time. Theirs is a history shaped by resilience and adaptation, and marked by loss and a thread of loneliness. Constructive lives. And lives slightly apart. Never quite at home.

Notes

1Maria Ember, oral history conducted by author, Paris, 28 and 31 May 1987.

2Lena Jedwab Rozenberg, Girl with Two Landscapes: The Wartime Diary of Lena Jedwab, 1941-1945 (New York and London: Holmes & Meier, 2002).

3Ibid.

4Ibid.

5Letter from Hanna-Ruth Klopstock to Elisabeth Luz, 24 August 1954, collection author. [Letter # 368b]

6Letter from Hanna-Ruth Klopstock to Elisabeth Luz, 7 December 1954, collection author. [Letter # 370]

7C.L. Lang, “Second Start in France,” in Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain, ed., Dispersion and Resettlement: The Story of the Jews from Central Europe (London: Association of Jewish Refugees in Great Britain, 1955).

8Werner Rosenstock, “Between the Continents,” in Dispersion and Resettlement.

9Mariánka May-Zadikow, oral history conducted by author, New Paltz, N.Y., 8-9 November 2000.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.