10 July 2023

In November 2022, the world’s population surpassed 8 billion people, having grown by 1 billion since 2010. Reaching this milestone raises important questions concerning the impact of human activities on the planet and its ability to sustain life for humans and other species.

Environmental impacts depend on both human numbers and human activities

Humanity’s impact on the Earth’s environment is a product of the number of inhabitants, how much each person consumes and the technology used to meet that level of consumption. Reducing our total environmental impact can be achieved only by modifying one or more of these components.

The level of development and well-being that many high-income countries enjoy today has been achieved largely through highly resource-intensive patterns of consumption and production, which are not sustainable or replicable on a global scale. With today’s technologies, our planet could not sustainably support even its current population if average global consumption were on par with the levels of today’s high-income countries.

Environmental damage often arises from economic processes that lead to higher standards of living. This is true especially when the full social and environmental costs, such as damage from pollution, are not factored into economic decisions about production and consumption. Population growth amplifies such pressures by adding to total economic demand.

The rising demand for food illustrates the complex relationship between population growth and the environment. Population size has always been a major driver of total food demand. Fortunately, for several decades, global food production has grown more rapidly than population. Currently, enough food is being produced worldwide to feed everyone, yet hunger, malnutrition and food insecurity remain major concerns due primarily to failures of distribution and unequal access.

While population growth is a major driver of the increasing demand for food, changes in the amount and types of food consumed have also had a significant impact. As average incomes have increased, diets have shifted to include both more calories and more varied and resource-intensive foods. These changes have had negative environmental impacts in terms of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, loss of biodiversity, and water and soil pollution.

Ending hunger and addressing food insecurity will require a holistic approach that focuses on sustainably increasing agricultural productivity, reducing food loss and waste, and strengthening food system supply chains and infrastructure. Shifting towards healthier, more sustainable, plant-based diets can make an important contribution to reducing the environmental damage caused by the current global food system, which accounts for between one quarter and one third of total GHG emissions.

Consumption growth in richer countries versus population growth in the poorest countries

It has become increasingly clear that human activities are causing climate change. The burning of fossil fuels, which have provided most of the energy needed for economic development, releases GHGs, mainly in the form of carbon dioxide (CO₂). Indeed, there is a near-linear relationship between cumulative anthropogenic CO₂ emissions and the observed increase in average temperatures.

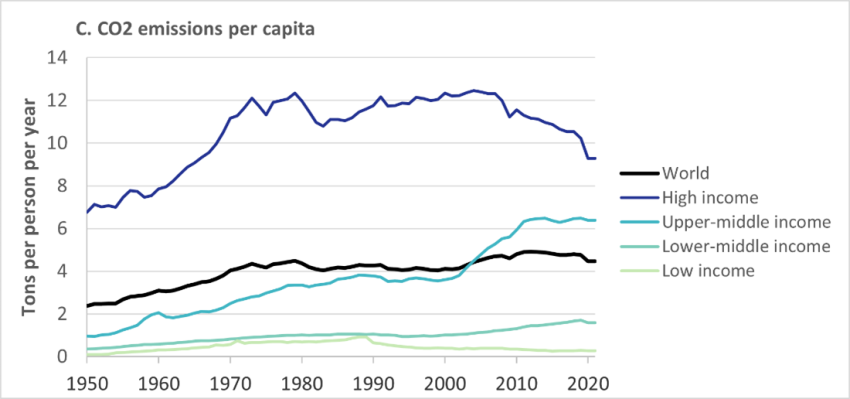

Population growth is one of the main drivers of increasing emissions. It is worth noting, however, that the countries emitting the largest per capita quantities of GHGs have been, to date, those where the average income is high and where the population is now growing slowly if at all, not those where the average income is low and the population is still growing rapidly.

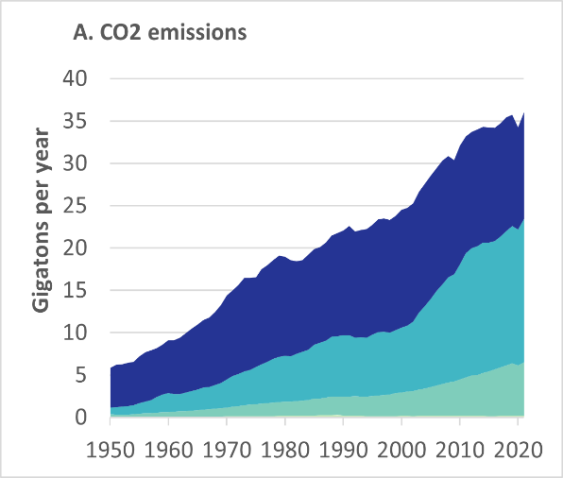

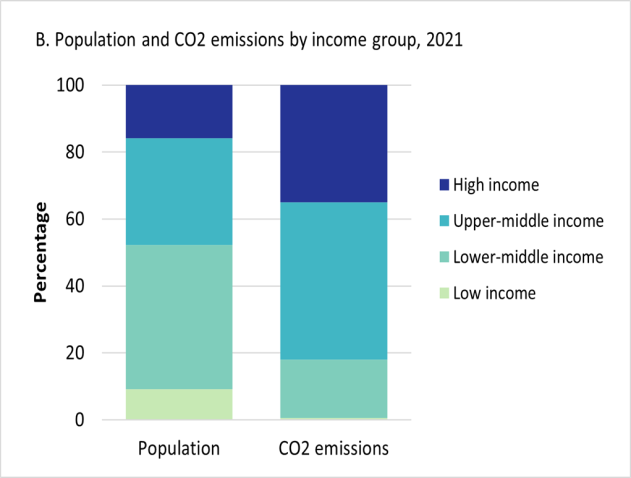

As of 2021, high-income and upper-middle-income countries, which together comprise 48 per cent of the world’s population, were responsible for about 82 per cent of the CO₂ added to the atmosphere each year (figure B, below). Low-income and lower-middle-income countries, where most future population growth is projected to take place, have so far contributed significantly less to these emissions, both in total (figure A, above) and per person (figure C, below).

In the coming decades, as the rate of global population growth continues to decline, population change is expected to become less and less important as a driver of rising GHG emissions. Meanwhile, trends in GDP per capita, energy efficiency and carbon intensity will become increasingly important.

Sustainability requires mitigating the environmental damage caused by human activities

One of the biggest challenges for the future is that the energy consumption of low-income and lower-middle-income countries will need to increase substantially if they are to develop economically and to achieve the Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. To end poverty and hunger, and to ensure that all people enjoy long and healthy lives and have access to a quality education and decent work, the economies of low-income and lower-middle-income countries will need to grow much more rapidly than their populations, requiring greatly expanded investments in infrastructure as well as increased access to affordable energy and modern technology in all sectors.

To achieve this accelerated growth, it will be essential for these countries to receive the necessary financial and technical assistance to ensure that their economies can grow while increasing their resilience and building their capacity to mitigate the causes, and adapt to the effects, of climate change. It is critical to ensure that their future economic growth is powered by clean sources of energy and does not replicate the over-reliance on fossil-fuel energy, which is the principal cause of the current climate crisis.

In the 2030 Agenda, Governments agreed on the importance of moving towards sustainable patterns of consumption and production, with the developed countries taking the lead and with all countries benefiting from the process. More affluent countries bear the greatest responsibility for moving rapidly to achieve net-zero emissions and for implementing strategies to decouple human economic activity from environmental degradation.

Population trends are relatively predictable and difficult to change

In the coming decades, it is expected that the world’s population will continue to grow, albeit at a progressively slower pace. Projections by the United Nations suggest that the global population could rise to around 10.4 billion in the 2080s, after which it may stabilize or begin a gradual decline.

Over the next 30 years, trends in world population can be projected with confidence, since most people who will be alive have already been born. On a global scale, population growth in this period will be driven mostly by the momentum of past growth. Beyond three decades, however, the trend in global population size will depend increasingly on the future course of mortality and fertility. Therefore, although reductions in fertility over the next few years can have only a limited effect on global trends between now and 2050, such changes could have important consequences for the size of the global population in the second half of the century, since the impact of fertility cumulates from one generation to the next.

Even though changes in fertility are unlikely to have a major effect on population trends at the global scale over the next 30 years, the near-term impact of a fertility reduction can be more substantial for countries with relatively high levels of fertility today. For these countries, there is both greater uncertainty regarding future population trends and a greater potential for slowing growth through a reduction in fertility. In such cases, a sustained drop in the fertility level would not only slow the growth of the total population in the near term; it would also have important short-term impacts on the population age distribution, lowering the share of children in the population and allowing greater investments per child in health care, education and other critical services.

Demographic transition is an integral part of sustainable development

Achieving the Goals and targets of the 2030 Agenda, especially those related to reproductive health, education and gender equality, can help to accelerate the demographic transition towards longer lives and smaller families, in part by empowering people to make critical choices about family formation and childbearing. Today, however, millions around the globe, mostly in low-income and lower-middle-income countries, lack access to the information and services needed to determine whether and when to have children.

Ensuring that individuals, in particular women, are able to decide the number of children that they will have and the timing of their births can markedly improve well-being and help to disrupt intergenerational cycles of poverty. Beyond facilitating a fertility decline, better access to reproductive health care, including safe and effective methods of family planning, can accelerate countries’ economic and social development.

Greater efforts are needed to reduce the unmet need for family planning, to raise the minimum legal age at marriage, to integrate family planning and safe motherhood programmes into primary health care, and to improve female education and employment opportunities. Progress in these areas will facilitate a more rapid fertility decline in low-income countries. Given appropriate policies, a lower fertility level will enable these countries to reap a demographic dividend—in the form of faster per-capita economic growth—thanks to an increasing concentration of population in the working ages.

Ultimately, planetary health and the sustainability of our economic system will depend on the social, demographic, economic and environmental choices that we make. Each of these dimensions is important and can aggravate or mitigate the impact of the others. However, it is not necessary to choose between them. We can improve our prospects for achieving a sustainable future by reducing our reliance on fossil fuels; moving away from unsustainable patterns of consumption and production; ensuring access to quality education, health care and decent work; promoting gender equality; and ensuring that those who wish to have smaller families or to postpone childbearing are able to do so.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.